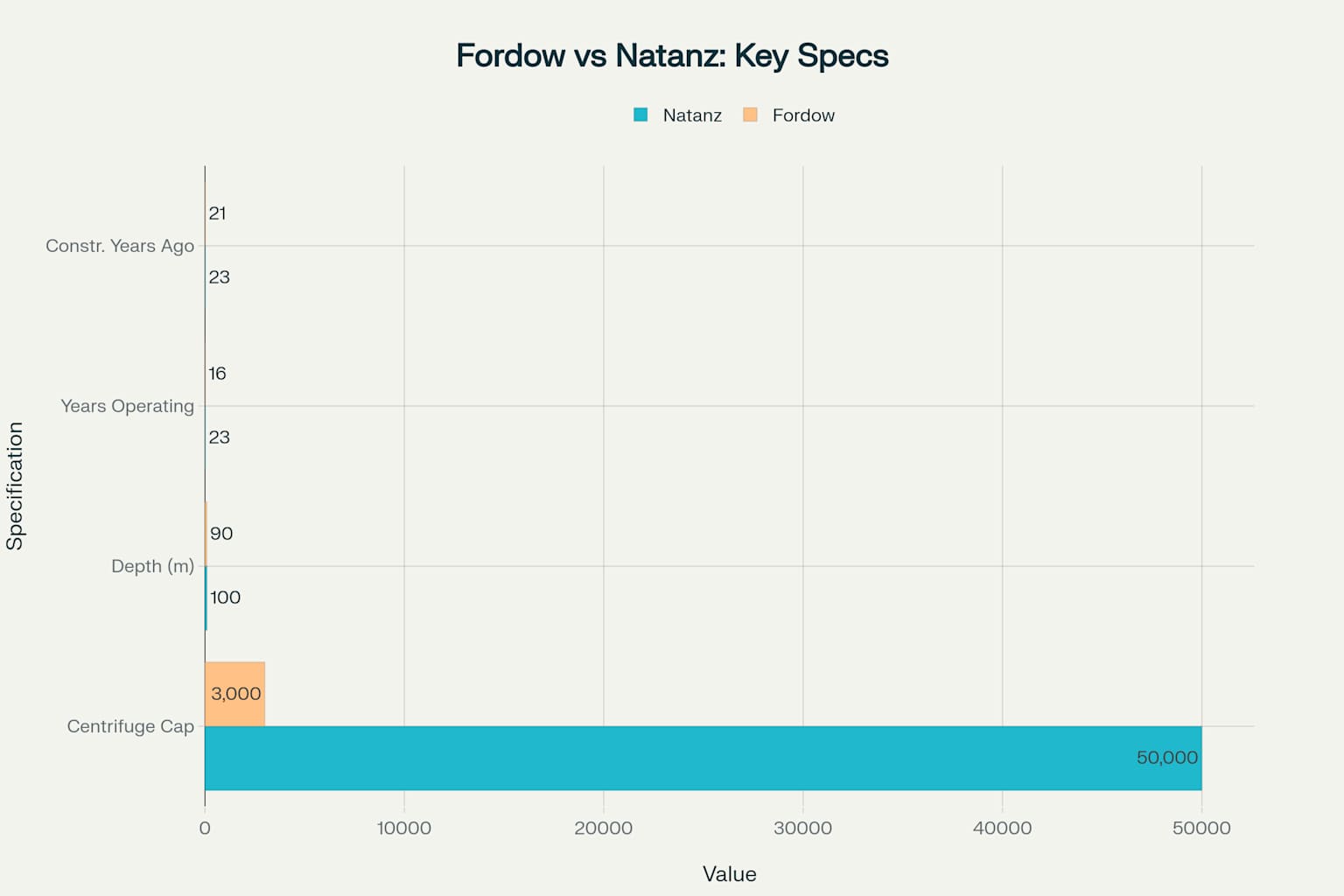

Iran’s nuclear program centers on two primary uranium enrichment facilities that represent fundamentally different approaches to nuclear capability development 12. While Natanz operates as a large-scale production facility with approximately 50,000 centrifuges, Fordow functions as a compact, heavily fortified site housing just 3,000 centrifuges buried deep within a mountain 34. The smaller facility, however, poses the greater strategic threat due to its proximity to weapons-grade uranium production and virtual immunity to conventional military strikes 56.

Map displaying the locations of key nuclear installations and major cities across Iran.

Geographic Distribution of Iran’s Nuclear Infrastructure

Iran’s nuclear facilities span across the country’s diverse terrain, with each location strategically chosen for specific operational and security advantages 7. The two primary enrichment sites occupy positions approximately 200 kilometers apart in Iran’s central region 13. Natanz sits in the relatively flat terrain near the city of Natanz, 160 kilometers north of Isfahan, while Fordow nestles into the mountainous landscape 30 kilometers northeast of the holy city of Qom 84.

Map showing the locations of Iran’s various nuclear facilities, including enrichment plants at Fordow and Natanz.

The geographic separation serves multiple strategic purposes for Iran’s nuclear program 79. Distance between facilities complicates potential military targeting while the varied terrain provides different types of natural protection 7. Fordow benefits from the natural fortress of the Elbourz mountain range, while Natanz has evolved to include both exposed above-ground facilities and newer underground installations 107.

The Tale of Two Nuclear Philosophies

Natanz: The Industrial Scale Approach

Natanz represents Iran’s commitment to large-scale uranium enrichment capability 83. Construction began around 1999-2000, making it Iran’s first major enrichment facility 1112. The complex consists of two main components: the Fuel Enrichment Plant (FEP) and the Pilot Fuel Enrichment Plant (PFEP) 813.

The facility’s design prioritizes volume over protection 83. Its above-ground structures house thousands of centrifuges in industrial-scale cascade configurations 814. Recent expansions include new underground tunnels extending more than 100 meters deep into the nearby Karkas Mountains 107.

Fordow: The Fortress Strategy

Fordow embodies a completely different strategic philosophy focused on survivability and rapid weaponization capability 62. Construction likely began between 2002 and 2004, though Iran only acknowledged its existence in 2009 after Western intelligence agencies detected the project 1516. The facility was originally designed as an Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps missile base before conversion to uranium enrichment 34.

The site’s location 80 to 110 meters underground within limestone and metamorphic rock formations provides maximum protection against aerial attack 57. Engineering documents from the Iranian nuclear archive reveal sophisticated blast and debris traps designed specifically to survive bombardment 1617.

Comparison of key technical specifications between Iran’s Fordow and Natanz nuclear facilities

Discovery Timeline and Secrecy Patterns

The revelation of both facilities follows distinct patterns that illuminate Iran’s strategic thinking 1811. Natanz was exposed in 2002 by opposition groups, forcing Iran to acknowledge a previously secret enrichment program 89. This exposure occurred relatively early in the facility’s development, limiting Iran’s ability to operate in complete secrecy 1119.

Fordow remained hidden for nearly seven additional years 415. Western intelligence agencies discovered construction activity through satellite imagery dating back to 2002, but Iran successfully concealed the facility’s nuclear purpose until 2009 1512. This extended secrecy period allowed Iran to complete construction and begin operations before international scrutiny intensified 1620.

The timing of Fordow’s revelation coincided with heightened international pressure over Iran’s nuclear program 1819. Iran’s decision to acknowledge the facility came only after realizing that Western intelligence had comprehensive knowledge of its existence and capabilities 612.

Enrichment Capabilities and Strategic Implications

Current Production Levels

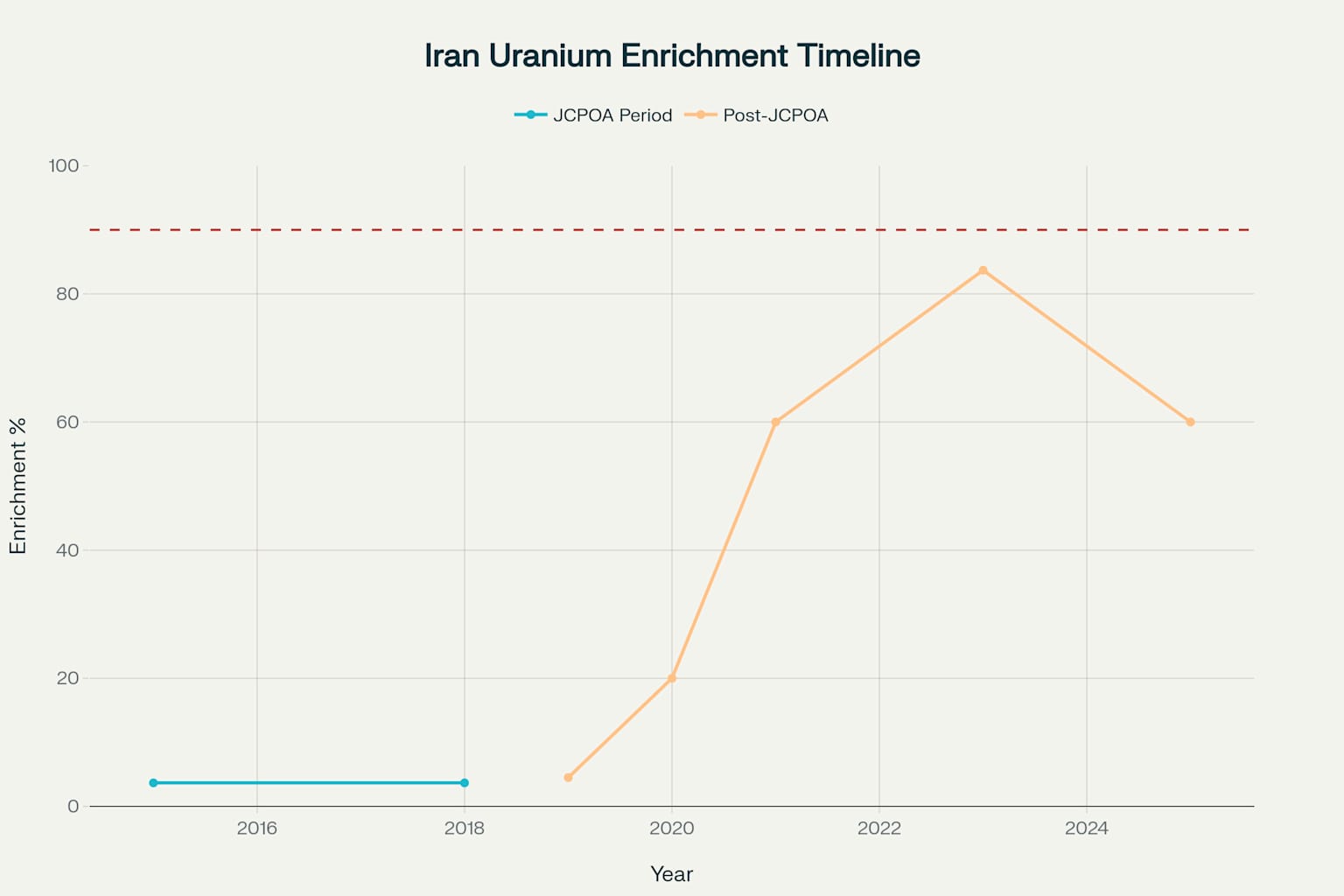

Iran currently produces approximately 37.5 kilograms of 60 percent enriched uranium monthly across both facilities 1421. Fordow contributes the majority of this production at 33.5 kilograms per month, despite housing significantly fewer centrifuges than Natanz 1422. This production rate reflects the facility’s focus on high-level enrichment rather than volume processing 214.

Iran’s uranium enrichment escalation timeline from JCPOA compliance to near weapons-grade levels

The International Atomic Energy Agency has detected uranium particles enriched to 83.7 percent at Fordow, representing the closest Iran has publicly acknowledged approaching weapons-grade levels 62. This detection occurred during unannounced inspections in 2023, indicating Iran’s capability to produce near-weapons-grade material 323.

Weaponization Timeline

Analysis of Iran’s current stockpile reveals alarming breakout capabilities 2124. With existing 60 percent enriched uranium reserves, Iran could produce weapons-grade material for nine nuclear weapons within three weeks 2124. Fordow specifically could generate its first 25-kilogram quantity of weapons-grade uranium in as little as two to three days 221.

This rapid weaponization capability stems from the physics of uranium enrichment 2523. The step from 60 percent to 90 percent weapons-grade uranium requires significantly less time and effort than earlier enrichment stages 2324. Iran’s accumulation of 60 percent material represents completion of approximately 90 percent of the work needed for weapons-grade uranium 2524.

Vulnerability Assessment and Military Implications

Fordow’s Defensive Advantages

Fordow’s underground location provides unprecedented protection among Middle Eastern nuclear facilities 517. The facility lies beneath an estimated 80 to 110 meters of mountain rock, making it effectively immune to conventional bunker-busting weapons in Israeli possession 520. Even Israel’s most powerful 5,000-pound bunker-busters cannot penetrate such depths 1720.

Military analysts assess that only the United States possesses weapons capable of potentially damaging Fordow 526. The GBU-57 Massive Ordnance Penetrator, weighing 30,000 pounds, represents the sole conventional weapon that might reach the facility’s depths 2617. Even this weapon would require multiple precise strikes and cannot guarantee complete destruction 56.

Natanz’s Exposure and Recent Damage

Natanz presents a markedly different vulnerability profile due to its mixed above-ground and underground configuration 827. Israeli strikes in June 2025 successfully destroyed the facility’s above-ground Pilot Fuel Enrichment Plant and caused significant damage to electrical infrastructure 2227. The attacks resulted in both radiological contamination within the facility and chemical toxicity from uranium hexafluoride compounds 2213.

Satellite imagery comparing the Natanz nuclear facility before and after an incident.

The facility’s underground components suffered less damage but face ongoing operational challenges 2713. Power system destruction has complicated restart efforts while contamination requires extensive cleanup before normal operations can resume 2227. These vulnerabilities highlight the strategic advantage of Fordow’s fully underground design 57.

Technical Specifications and Operational Differences

Centrifuge Technology and Deployment

Both facilities employ multiple generations of Iranian-developed centrifuges 1428. Natanz primarily utilizes first-generation IR-1 centrifuges alongside newer IR-2m, IR-4, and IR-6 models 1428. The facility’s large scale allows for extensive cascade configurations that maximize total enrichment capacity 814.

Fordow operates a more selective centrifuge deployment focused on advanced models 1428. The facility emphasizes IR-6 centrifuges, which provide approximately ten times the enrichment capacity of older IR-1 models 2822. This technological focus allows Fordow to achieve high enrichment levels despite its smaller physical footprint 214.

Production Flexibility and Adaptation

Fordow demonstrates superior operational flexibility for weapons-oriented production 221. The facility can rapidly reconfigure from civilian-justified enrichment levels to weapons-grade production 2124. Its interconnected cascade system allows for seamless progression from natural uranium through multiple enrichment stages 2114.

Natanz serves multiple enrichment functions simultaneously but lacks Fordow’s rapid reconfiguration capability 1413. The facility produces uranium at 2, 5, and 60 percent enrichment levels for various stated civilian purposes 1314. This diversity provides diplomatic cover but complicates rapid conversion to pure weapons production 2324.

International Response and Diplomatic Implications

IAEA Monitoring and Compliance Issues

The International Atomic Energy Agency maintains continuous monitoring at both facilities, though with varying degrees of access and cooperation 2713. Recent Iranian decisions to limit inspector access and remove monitoring equipment have heightened international concerns 2927. The IAEA Board of Governors formally found Iran in non-compliance with its nuclear obligations for the first time in twenty years 2930.

Iran’s response to international pressure includes threats to establish additional enrichment facilities in secure locations 29. This escalation pattern suggests Iran may replicate Fordow’s hardened design at new sites currently under construction 1029. Satellite imagery reveals ongoing tunnel construction at Natanz that may create Fordow-like protection for expanded operations 1027.

Sanctions and Diplomatic Pressure

International sanctions specifically target Iran’s nuclear program components, including both facilities and their supply chains 3031. The comprehensive sanctions framework includes restrictions on nuclear-related materials, technology transfers, and financial transactions supporting the program 3032. These measures aim to slow progress while encouraging diplomatic engagement 3230.

Recent diplomatic efforts have failed to restore the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action framework that previously limited Iran’s nuclear activities 3224. The 2018 U.S. withdrawal from the nuclear deal removed key constraints on Iran’s enrichment program 3219. Subsequent Iranian violations have effectively eliminated most agreement provisions 1925.

Strategic Assessment and Future Implications

The Fordow Advantage in Nuclear Deterrence

Fordow represents Iran’s most credible nuclear deterrent capability due to its combination of protection and rapid weaponization potential 220. The facility’s immunity to conventional attack provides Iran with confidence that it can maintain nuclear options regardless of military pressure 56. This assurance may encourage more aggressive regional behavior and nuclear program expansion 312.

The facility’s compact design and focused mission make it ideal for weapons production under crisis conditions 2124. Unlike Natanz’s multiple functions and larger footprint, Fordow can concentrate entirely on high-level enrichment without operational distractions 214. This specialization provides Iran with a reliable path to nuclear weapons capability 2124.

Regional Proliferation Implications

Iran’s nuclear advancement, particularly at Fordow, threatens to trigger wider regional proliferation 31. Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states have expressed interest in nuclear technology development in response to Iranian capabilities 31. Egypt and Turkey maintain nuclear research programs that could serve as foundations for weapons development 31.

The Middle East’s history of conflict and regional rivalries creates multiple incentives for nuclear weapons acquisition 31. Iran’s demonstration of successful nuclear program advancement despite international pressure may encourage other regional actors to pursue similar capabilities 31. Fordow’s success as a protected facility provides a potential model for other regional nuclear programs 731.

Current Crisis and Military Calculations

Israeli Strategic Dilemma

Israel faces an unprecedented strategic challenge in addressing Iran’s nuclear program 126. Fordow’s protection makes unilateral Israeli action largely ineffective while Natanz’s partial destruction has limited impact on Iran’s weapons timeline 527. The facility’s continued operation demonstrates Iran’s commitment to maintaining nuclear advancement despite military pressure 222.

Israeli military planners recognize that comprehensive action against Iran’s nuclear program requires either U.S. participation or acceptance of incomplete results 2617. Fordow specifically demands American bunker-busting capabilities that Israel does not possess 526. This dependency complicates Israeli decision-making and potentially delays military action 126.

Iranian Strategic Calculations

Iran’s nuclear strategy increasingly centers on Fordow as the program’s crown jewel 221. The facility’s survival during recent Israeli attacks validates its design philosophy and strategic value 622. Iran can maintain confidence in its nuclear options as long as Fordow remains operational and protected 52.

The facility’s rapid weaponization capability provides Iran with escalation options during regional crises 2124. Knowledge that weapons-grade uranium production can begin within days offers significant leverage in diplomatic negotiations 223. This capability may encourage Iranian risk-taking in regional conflicts 3121.

Conclusion: The Paradox of Size and Significance

The comparison between Fordow and Natanz illuminates a fundamental principle of nuclear strategy: protection often matters more than production capacity 52. While Natanz’s 50,000 centrifuges represent impressive industrial capability, Fordow’s 3,000 centrifuges pose the greater immediate threat to regional stability and nonproliferation efforts 621.

Fordow’s combination of physical protection, technological sophistication, and weapons-focused mission makes it Iran’s most dangerous nuclear facility 52. The international community’s inability to neutralize this facility through conventional means highlights the challenges of preventing nuclear proliferation in an era of advanced engineering and determined adversaries 2631.

The strategic lesson extends beyond Iran’s specific case to broader questions of nuclear facility design and international security 731. As nuclear technology spreads and construction techniques advance, the Fordow model may inspire similar facilities in other regions and countries 31. The smaller, hardened facility represents a new paradigm in nuclear facility protection that challenges traditional approaches to nonproliferation enforcement 531.

Footnotes

-

https://www.timesofisrael.com/pm-israel-will-hit-all-nuclear-facilities-has-destroyed-half-of-irans-launchers/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

https://www.csis.org/analysis/three-things-will-determine-irans-nuclear-future-fordow-just-one-them ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11 ↩12 ↩13 ↩14 ↩15 ↩16

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuclear_facilities_in_Iran ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6

-

https://www.cnn.com/2025/06/17/middleeast/iran-fordow-nuclear-site-latam-hnk-intl ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/bombing-irans-underground-fordo-nuclear-plant-effective-expert/story?id=123013773 ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11 ↩12 ↩13 ↩14

-

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/6/19/what-is-irans-fordow-nuclear-facility-and-could-us-weapons-destroy-it ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8

-

https://dailygalaxy.com/2025/06/why-does-iran-hide-its-nuclear-sites-in-these-mountains-geology-exposes-the-ultimate-invisible-shield/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natanz_Nuclear_Facility ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8

-

https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/irans-natanz-tunnel-complex-deeper-larger-than-expected/8 ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_the_nuclear_program_of_Iran ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2009-12/iaea-rebukes-iran-over-secret-facility ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

https://www.armscontrol.org/blog/2025-06-16/irans-nuclear-facilities-updates ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6

-

https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/analysis-of-iaea-iran-verification-and-monitoring-report-may-2025/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11 ↩12 ↩13

-

https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/iaea-report-on-iran-fordow-enrichment-plant-at-advanced-stage-of-constructi/8 ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/the-fordow-enrichment-plant-aka-al-ghadir/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

https://www.foxnews.com/world/how-bunker-buster-bombs-work-how-could-destroy-irans-fordow-nuclear-site ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

https://www.iranwatch.org/our-publications/weapon-program-background-report/history-irans-nuclear-program ↩ ↩2

-

https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/timeline-nuclear-diplomacy-iran-1967-2023 ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

https://gulfnews.com/world/mena/inside-iran-s-hidden-nuclear-fortress-what-to-know-about-fordow-1.500168783 ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

https://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/Analysis_of_May_2025_IAEA_Iran_Verification_Report_FINAL.pdf ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11 ↩12 ↩13

-

https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/statements/iaea-director-general-grossis-statement-to-unsc-on-situation-in-iran ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7

-

https://www.lemonde.fr/en/les-decodeurs/article/2025/06/19/how-close-is-iran-to-nuclear-weapons_6742494_8.html ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

https://www.cnn.com/2024/07/19/politics/blinken-nuclear-weapon-breakout-time ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10

-

https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2024-02/news/iran-accelerates-highly-enriched-uranium-production ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2025/06/20/iran-israel-war-trump-netanyahu-fordow/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7

-

https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/pressreleases/update-on-developments-in-iran ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8

-

https://iranprimer.usip.org/blog/2021/nov/22/explainer-controversy-over-iran’s-centrifuges ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

https://www.npr.org/2025/06/12/nx-s1-5431395/iran-nuclear-enrichment-un-compliance ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_sanctions_against_Iran ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

https://npolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Nuclear_Proliferation_Prospects_in_the_Middle_East_to__2025.pdf ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11 ↩12 ↩13

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joint_Comprehensive_Plan_of_Action ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4