In the shadowy world of nuclear proliferation, few figures loom as large as Abdul Qadeer Khan, the Pakistani nuclear physicist whose clandestine network transformed the global nuclear landscape and laid the groundwork for Iran’s most controversial nuclear facility 123.

Portrait of Abdul Qadeer Khan, the Pakistani nuclear physicist central to the A.Q. Khan network.

The Father of Pakistan’s Nuclear Bomb

Born in Bhopal, India in 1936, Abdul Qadeer Khan migrated to Pakistan following the 1947 partition of the subcontinent 3. After completing advanced studies in metallurgical engineering in Europe, Khan’s career took a fateful turn when he joined URENCO, a British-German-Dutch uranium enrichment consortium in the Netherlands 45.

During his time at URENCO in the 1970s, Khan gained unprecedented access to highly sensitive centrifuge designs and technical specifications that would later become the foundation of not just Pakistan’s nuclear program, but several others around the world 46.

When India conducted its first nuclear test in 1974, Khan reached out to then-Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, offering his expertise to help Pakistan develop its own nuclear deterrent 7. Bhutto famously declared that Pakistanis would “eat grass” if necessary to match India’s nuclear capability 78.

In December 1975, Khan left the Netherlands for Pakistan, taking with him stolen blueprints for uranium centrifuges and lists of European suppliers who could provide critical components 5. This technological heist would become one of the most consequential acts of nuclear espionage in history 96.

A.Q. Khan, the Pakistani nuclear scientist and central figure of the A.Q. Khan network, waving.

The Birth of a Nuclear Black Market

Upon his return to Pakistan, Khan established the Engineering Research Laboratory (later renamed Khan Research Laboratories) in Kahuta, where he developed Pakistan’s uranium enrichment program 58. The facility was constructed to house thousands of centrifuges based on the stolen URENCO designs, particularly the P-1 model 510.

Khan’s genius lay not just in his technical knowledge, but in his ability to establish a vast procurement network that could circumvent international export controls 11. Through front companies and intermediaries across Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, Khan sourced components that should have been impossible to obtain under nuclear non-proliferation regulations 212.

By the early 1980s, Pakistan had successfully produced highly enriched uranium, and on May 28, 1998, Pakistan conducted its first nuclear tests, with bomb cores built under Khan’s supervision 8. What few realized at the time was that Khan had been purchasing twice as many centrifuge components as needed for Pakistan’s own program 913.

This surplus of equipment and expertise would soon become the inventory for an unprecedented nuclear black market 1214. Through a complex network of suppliers, middlemen, and front companies spanning over 20 countries, Khan built what experts have called a “nuclear Walmart” 152.

Iran’s Nuclear Ambitions and the Khan Connection

Iran’s quest for nuclear technology began under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in the 1950s, but the Islamic Revolution of 1979 and the subsequent Iran-Iraq War altered its trajectory 16. By the late 1980s, Iranian leaders had decided to pursue a covert nuclear program that would include uranium enrichment capability 1617.

The breakthrough came in 1987, when representatives of the Khan network met with Iranian officials in Dubai and presented a handwritten one-page “menu” of nuclear offerings 1718. This initial deal included designs for the P-1 centrifuge, drawings and specifications for a complete centrifuge plant, and materials for 2,000 centrifuge machines 1719.

A vast array of gas centrifuges arranged in long rows, illustrating a uranium enrichment cascade.

Iran did not purchase everything on Khan’s list but bought one or two disassembled centrifuges along with critical drawings and specifications 17. The Iranians would use this “menu” as a shopping list for subsequent purchases from various suppliers over the years 1720.

A second major deal materialized between 1994 and 1995, when Iran received approximately 500 disassembled P-1 centrifuge machines and designs for the more advanced P-2 model 1719. These transfers gave Iran the fundamental knowledge and components needed to begin developing its own uranium enrichment program 1920.

The P-1 centrifuge that Khan provided to Iran was based on a first-generation Dutch design that he had stolen from URENCO 1910. Though not particularly efficient by modern standards, these machines became the foundation of Iran’s enrichment program and were later designated as IR-1 centrifuges by Iran 1920.

Rows of advanced centrifuges arranged in a cascade for uranium enrichment within an industrial facility.

Technical Specifications and Challenges

The P-1/IR-1 centrifuge design features a rotor assembly approximately 180 cm long with a diameter of 10.5 cm 2122. It consists of four aluminum rotor tubes connected by three maraging steel bellows, with aluminum end caps 2223.

These centrifuges were far from perfect - the design suffered from high failure rates and relatively low efficiency, producing only about 0.8-1 separative work units (SWU) per year 2422. For comparison, modern centrifuges used in commercial enrichment plants can produce 10-100 SWU per year 2526.

Iran struggled with the reliability issues inherent in the P-1 design 2724. The machines frequently broke down during operation, requiring Iran to develop a unique “Cascade Protection System” to cope with ongoing centrifuge failures 2728. This system would isolate failing centrifuges to prevent cascade-wide problems 2722.

Despite these challenges, the P-1/IR-1 centrifuges offered Iran a critical advantage: they could be produced in large numbers, allowing Iran to compensate for their inefficiency through volume 2724. Iran eventually installed thousands of these machines at its Natanz enrichment facility and later at Fordow 2029.

The Secret Mountain: Fordow Takes Shape

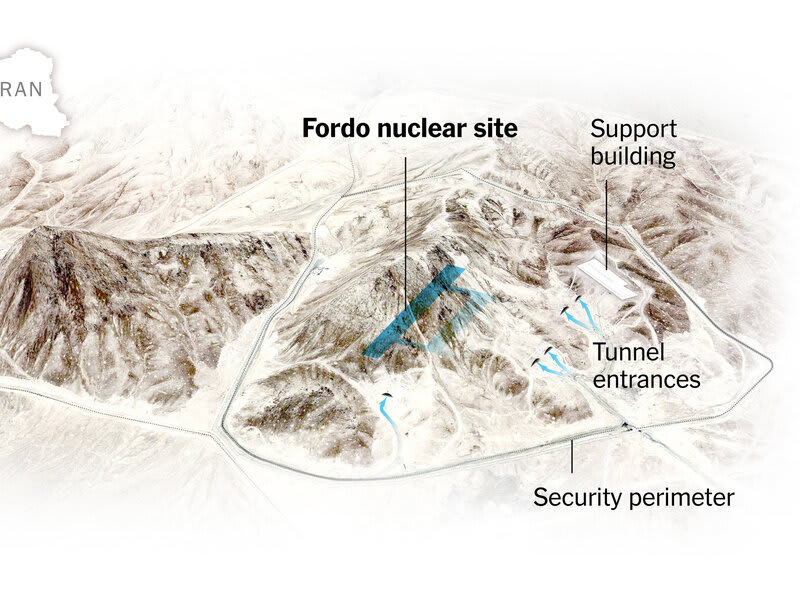

The Fordow Fuel Enrichment Plant represents one of the most controversial aspects of Iran’s nuclear program 3031. Unlike the Natanz facility, which Iran declared to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Fordow was built in secret, buried deep within a mountain near the holy city of Qom 3032.

An isometric diagram of Iran’s Fordow nuclear site, highlighting its underground location and key security features.

Construction of the Fordow facility likely began between 2002 and 2006, though Iran later claimed work started in the second half of 2007 3331. The site was originally a tunnel complex associated with Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) before being converted into a uranium enrichment facility 3234.

Documents revealed from Iran’s nuclear archive, seized by Israeli intelligence in 2018, indicate that Fordow (initially code-named “Al Ghadir”) was originally designed as part of Iran’s nuclear weapons program, intended to produce weapons-grade uranium for 1-2 nuclear weapons per year 3536.

Aerial view of Iran’s Fordow Fuel Enrichment Plant, built into rugged mountains for protection.

The facility is buried approximately 80-90 meters (260-295 feet) underground, protected by rock and reinforced concrete, making it largely immune to conventional airstrikes 3731. This depth was deliberately chosen to shield the facility from potential military attacks, a concern that Iran cited when explaining the site’s location to the IAEA 3330.

Satellite imagery and intelligence reports indicate that Fordow consists of two main enrichment halls, each designed to hold eight IR-1 centrifuge cascades, for a total of approximately 3,000 centrifuges 3432. The site also includes support facilities and infrastructure necessary for uranium enrichment operations 3238.

Aerial view of the Fordow nuclear facility under construction, showing its distinct grid-like underground foundation.

International Discovery and Response

In September 2009, Western intelligence agencies revealed that they had been monitoring the clandestine Fordow facility 3331. Faced with this exposure, Iran notified the IAEA about the plant just days before President Barack Obama, British Prime Minister Gordon Brown, and French President Nicolas Sarkozy publicly announced its existence 3339.

Obama described the site as having a “size and configuration inconsistent with a peaceful program,” highlighting international concerns about Iran’s nuclear intentions 3140. The discovery of Fordow significantly escalated tensions and reinforced suspicions about the true nature of Iran’s nuclear ambitions 3940.

The revelation prompted intensified diplomatic efforts, eventually leading to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2015 4139. Under this agreement, Iran agreed to convert Fordow into a nuclear research center and cease uranium enrichment at the site for 15 years 4129.

However, after the United States withdrew from the JCPOA in 2018, Iran resumed and expanded enrichment activities at Fordow 2933. By 2023, IAEA inspectors detected uranium particles enriched to 83.7% purity at the facility - dangerously close to the 90% threshold considered weapons-grade 3042.

Iranian IR6 and IR6s centrifuges on display.

The Enduring Legacy of Khan’s Network

A.Q. Khan’s network represents a watershed moment in nuclear proliferation 1512. For the first time in history, a private enterprise controlled all the necessary elements of a nuclear weapons program, from design to production 1213. This democratization of nuclear technology fundamentally altered the global security landscape 214.

The consequences of Khan’s transfers to Iran continue to reverberate today 4344. The IR-1 centrifuges derived from Khan’s P-1 design still form the backbone of Iran’s enrichment program, particularly at Fordow 4534. Although Iran has since developed more advanced centrifuge models, these improvements build upon the foundation laid by Khan’s initial transfers 4645.

In the decades since Khan’s network was exposed and dismantled, Iran has achieved self-sufficiency in centrifuge production and design 4645. The progression from the basic IR-1 to advanced models like the IR-6 demonstrates how Iran leveraged Khan’s initial assistance into an indigenous nuclear capability 4546.

A large uranium enrichment facility with numerous rows of gas centrifuges arranged in a cascade.

Khan himself never expressed regret for his proliferation activities 311. After his network was exposed in 2004, he made a televised confession under pressure from the Pakistani government, but later recanted, claiming he had been made a scapegoat 13. He remained under house arrest until 2009 and died in 2021 at the age of 85 343.

The ghost of A.Q. Khan’s legacy lives on in the mountains of Fordow and in the continued international tensions surrounding Iran’s nuclear program 3947. His network’s transfers to Iran shortened the country’s path to potential nuclear weapons capability by years, if not decades 616.

Today, as international inspectors and intelligence agencies continue to monitor activities at Fordow, the facility stands as perhaps the most enduring and controversial monument to Khan’s nuclear proliferation network 4842. The centrifuges spinning beneath the mountain remain a testament to how one man’s actions can reshape global security for generations 152.

Footnotes

-

https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/aq-khan-dead-long-live-proliferation-network ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/10/10/abdul-qadeer-khan-nuclear-hero-in-pakistan-villain-to-the-west ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Abdul-Qadeer-Khan ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

https://www.moneycontrol.com/world/stolen-blueprints-smuggled-parts-and-black-market-how-father-of-pakistani-bomb-armed-iran-s-nuclear-program-article-13148029.html ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

https://www.npr.org/2021/10/10/1044859067/abdul-qadeer-khan-pakistan-nuclear-bomb-dies-at-85 ↩ ↩2

-

https://www.pbs.org/frontlineworld/stories/pakistan/nytimes03.html ↩ ↩2

-

https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/aq-khan-did-he-trade-nuclear-bomb-designs-for-money-or-out-of-defiance-50720 ↩ ↩2

-

https://www.rusi.org/publication/khan-network-lessons-and-consequences ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

https://isis-online.org/publications/southasia/nuclear_black_market.html ↩ ↩2

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuclear_program_of_Iran ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

https://www.iranwatch.org/our-publications/weapon-program-background-report/history-irans-nuclear-program ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6

-

https://outrider.org/nuclear-weapons/articles/scientist-who-sold-nuclear-technology ↩

-

https://iranprimer.usip.org/blog/2021/nov/22/explainer-controversy-over-iran’s-centrifuges ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

https://www.nti.org/analysis/articles/iranian-centrifuge-model-collection/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

https://www.princeton.edu/~aglaser/2008aglaser_sgsvol16.pdf ↩

-

https://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/A_Comprehensive_Survey_of_Irans_Advanced_Centrifuges_December_2021.pdf ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

https://www.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/201388/bellows-bearings-and-rotors/ ↩

-

https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2014-06/features/agreeing-limits-irans-centrifuge-program-two-stage-strategy ↩

-

https://pubs.aip.org/physicstoday/article/61/9/40/413428/The-gas-centrifuge-and-nuclear-weapons ↩

-

https://www.langner.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/to-kill-a-centrifuge.pdf ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/irans-advanced-centrifuges/8 ↩

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fordow_Fuel_Enrichment_Plant ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

https://news.sky.com/story/fordow-what-we-know-about-irans-secretive-nuclear-mountain-and-how-israel-might-try-to-destroy-it-13385834 ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

https://www.cnn.com/2025/06/17/middleeast/iran-fordow-nuclear-site-latam-hnk-intl ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuclear_facilities_in_Iran ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/6/19/what-is-irans-fordow-nuclear-facility-and-could-us-weapons-destroy-it ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

https://www.nti.org/education-center/facilities/fordow-fuel-enrichment-plant/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/summary-of-report-the-fordow-enrichment-plant-aka-al-ghadir-1/8 ↩

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mossad_infiltration_of_Iranian_nuclear_archive ↩

-

https://www.ynetnews.com/health_science/article/bydahnzvgx ↩

-

https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/conversion-of-fordow-another-unfulfilled-hope-of-the-iran-nuclear-deal/8 ↩

-

https://thehill.com/policy/international/5359296-iran-fordow-nuclear-site-israel-iran-conflict/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

https://thebulletin.org/2009/11/a-technical-evaluation-of-the-fordow-fuel-enrichment-plant/ ↩ ↩2

-

https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/what-iran-nuclear-deal ↩ ↩2

-

https://www.timesofisrael.com/aq-khan-father-of-pakistans-nuclear-program-who-also-helped-iran-dies-at-85/ ↩ ↩2

-

https://www.iranwatch.org/our-publications/articles-reports/irans-nuclear-timetable-weapon-potential ↩

-

https://www.iranwatch.org/our-publications/weapon-program-background-report/irans-centrifuges-models-status ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/september-2022-highlights-of-survey-of-irans-advanced-centrifuges/8 ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/a-brief-history-of-sanctions-on-iran/ ↩

-

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/israel-iran-war-fordo-nuclear-site/ ↩