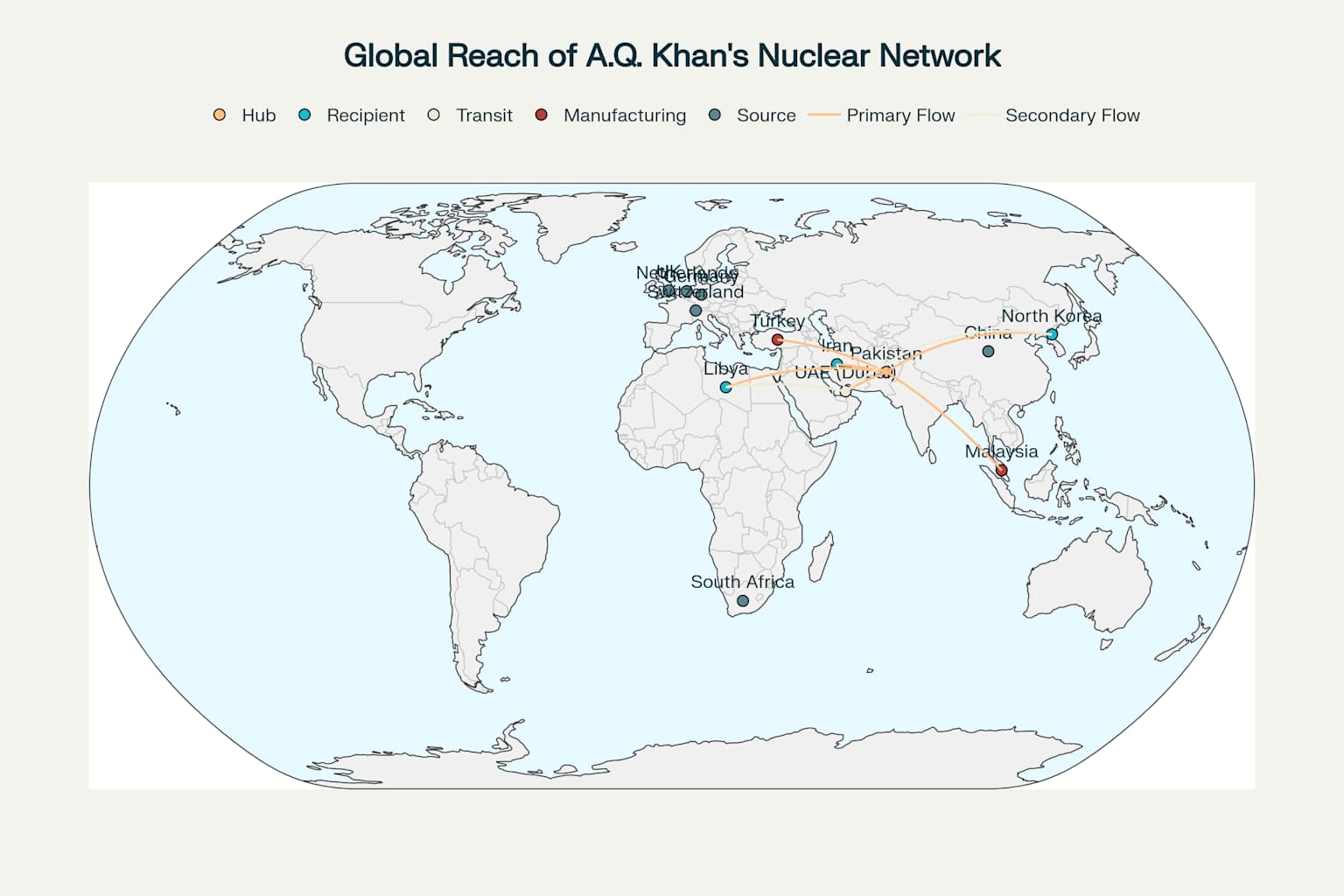

Abdul Qadeer Khan, widely regarded as the father of Pakistan’s nuclear program, transformed from a respected scientist to the mastermind behind history’s most dangerous nuclear proliferation network 12. His network spanned multiple continents and transferred critical nuclear technology to countries like Iran, Libya, and North Korea 34.

Abdul Qadeer Khan, the Pakistani nuclear scientist, waving to the camera.

Early Life and Education

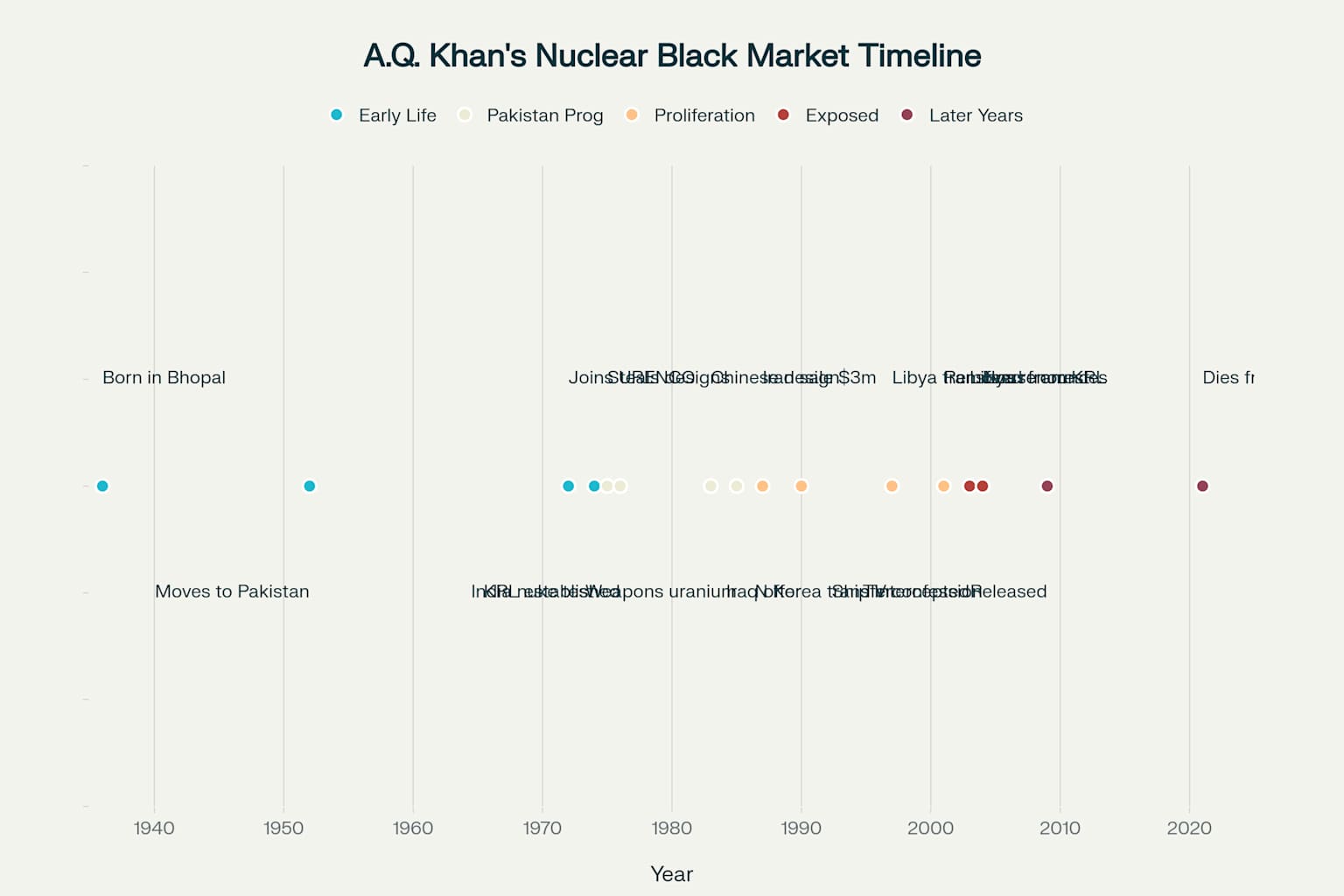

Born on April 1, 1936, in Bhopal, India, Khan would later immigrate to Pakistan in 1952 following the partition of the subcontinent 13. Khan’s academic journey took him to Europe, where he studied metallurgical engineering in West Berlin and later received a master’s degree from Delft University in the Netherlands in 1967 25.

In 1972, Khan completed his doctorate in metallurgical engineering from the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium, positioning him for his future role in nuclear technology 36. That same year, Khan began working at Physical Dynamic Research Laboratory (FDO), a subcontractor of Ultra Centrifuge Nederland (UCN), gaining access to highly sensitive uranium enrichment technology 78.

Abdul Qadeer Khan, a central figure in Pakistan’s nuclear program.

Theft of Nuclear Secrets

Khan’s career took a decisive turn in 1974 when India conducted its first nuclear test, codenamed “Smiling Buddha,” which alarmed neighboring Pakistan 910. Following India’s nuclear test, Khan wrote to Pakistani Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, offering his expertise to help Pakistan develop its own nuclear capability 711.

While working at URENCO, Khan gained unauthorized access to crucial centrifuge designs, particularly the advanced G-1 and G-2 models used for uranium enrichment 812. Dutch intelligence had begun monitoring Khan for suspicious activities, but this didn’t prevent him from stealing blueprints and supplier information for uranium centrifuges 1314.

On December 15, 1975, Khan abruptly left the Netherlands for Pakistan, taking with him copied blueprints for centrifuges and contact information for nearly 100 companies that supplied centrifuge components and materials 79. This theft would form the foundation of both Pakistan’s nuclear program and Khan’s future proliferation network 1314.

A.Q. Khan’s Nuclear Black Market: A Timeline of Key Events (1936-2021)

Building Pakistan’s Nuclear Program

Upon returning to Pakistan, Khan initially worked with the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) but soon faced conflicts with its leadership 158. In July 1976, Prime Minister Bhutto gave Khan autonomous control over Pakistan’s uranium enrichment program, and Khan founded the Engineering Research Laboratory (ERL), which would later be renamed Khan Research Laboratories (KRL) 73.

By 1978, Khan’s team developed working prototypes of P-1 centrifuges, adapted from the German G-1 designs he had acquired at URENCO, and Pakistan successfully enriched uranium for the first time at Khan’s facility in Kahuta 78. Throughout the early 1980s, Khan continued to improve Pakistan’s enrichment capabilities and acquired blueprints for a Chinese nuclear bomb design that had been tested in 1966 76.

By 1985, Pakistan had produced enough highly enriched uranium (HEU) for a nuclear weapon, achieving Khan’s primary goal of nuclear parity with India 16. Khan’s status in Pakistan rose to that of a national hero, with his laboratory renamed Khan Research Laboratories (KRL) in his honor in 1981 27.

Abdul Qadeer Khan, the central figure in Pakistan’s nuclear program.

From Importer to Exporter

In the mid-1980s, Khan transformed from an importer of nuclear technology to an exporter, creating a vast international network for nuclear proliferation 416. Khan began ordering twice the number of components necessary for Pakistan’s program, creating a surplus that could be sold to other countries 617.

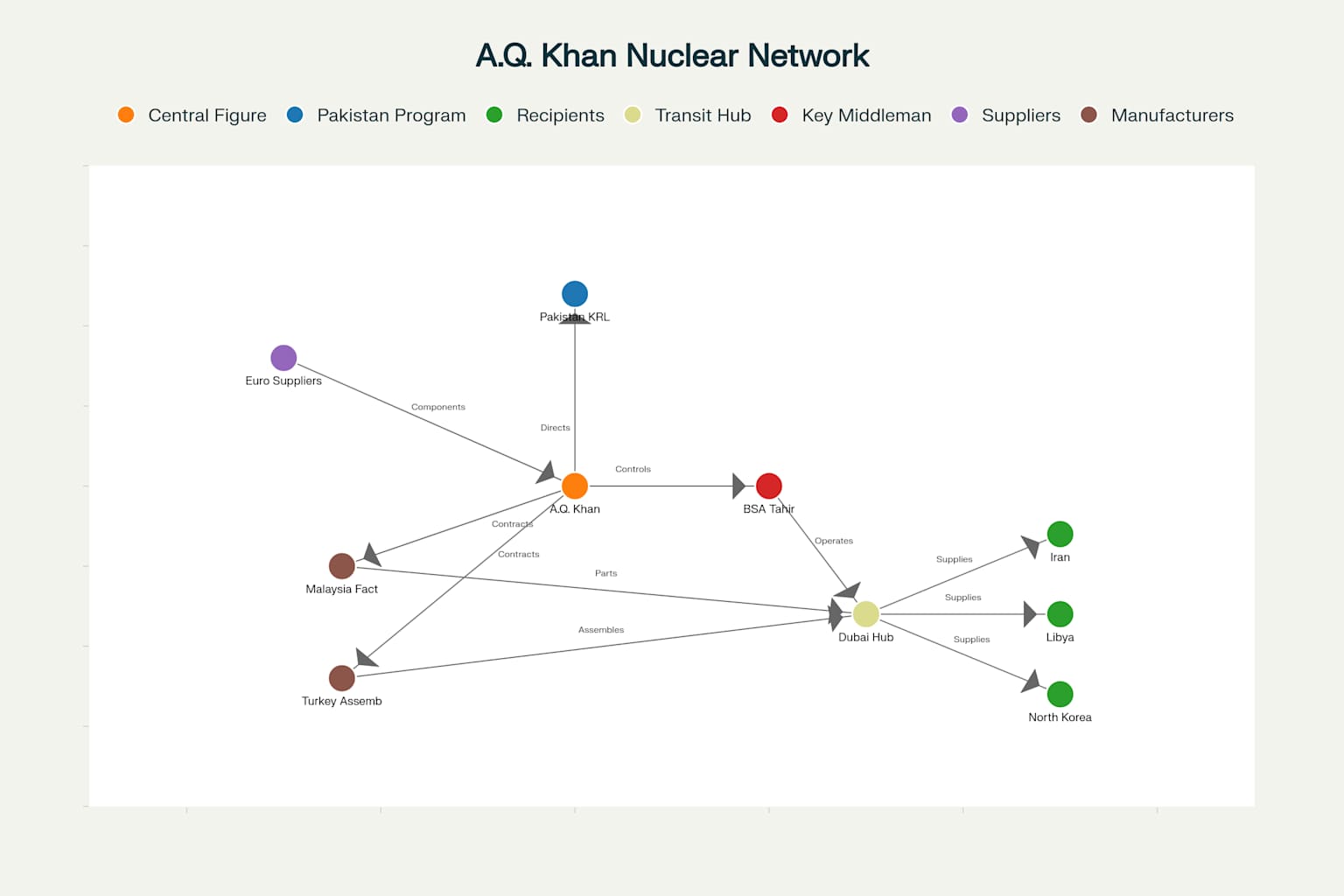

The network Khan established included suppliers, middlemen, and front companies in over 20 countries, forming a complex web of nuclear smuggling operations 418. Khan utilized many of the same procurement channels he had established for Pakistan’s program, but now reversed the flow to export centrifuge technology to other nations 196.

A key figure in Khan’s network was Buhary Syed Abu Tahir (B.S.A. Tahir), a Sri Lankan businessman based in Dubai who served as Khan’s chief lieutenant and middleman for nuclear deals 2021. Dubai emerged as the central transit hub for Khan’s network, where components could be repackaged and shipped to various destinations with false end-user certificates 1619.

Structure of A.Q. Khan’s Nuclear Proliferation Network

Proliferation to Iran

Khan’s first known involvement in nuclear proliferation began with Iran in the mid-1980s 619. In 1987, Khan reportedly offered Iran a comprehensive package of nuclear technologies for tens to hundreds of millions of dollars 64.

Iranian officials met with Khan’s associates in Dubai, where a deal was struck to provide Iran with disassembled centrifuges, drawings, descriptions, and specifications for production 419. According to B.S.A. Tahir’s later confession, Iran paid approximately $3 million in cash for P-1 centrifuge technology, which was delivered in two containers shipped from Dubai to Iran 206.

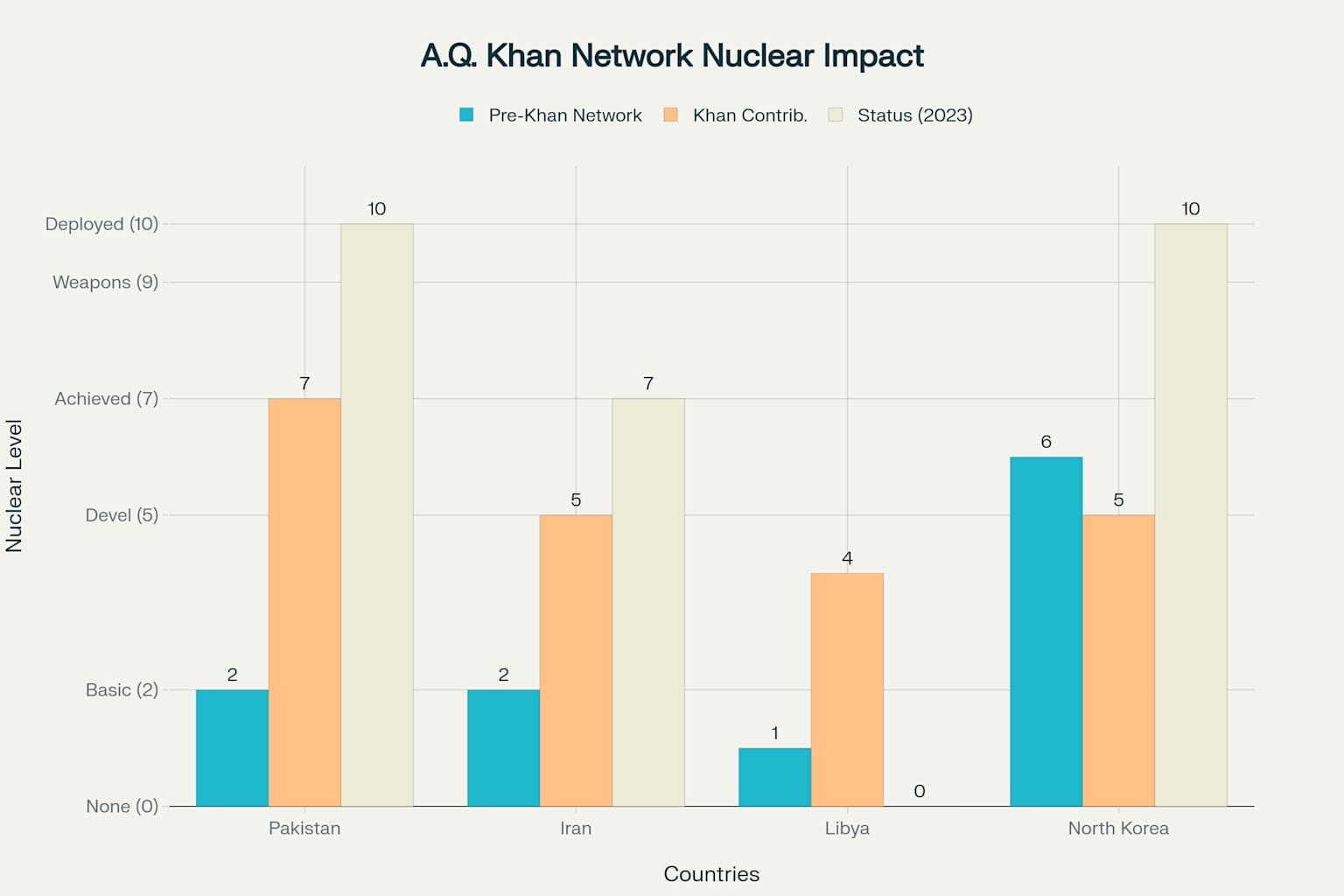

The transfers to Iran continued through the mid-1990s, when Iran received more advanced P-2 centrifuge designs and components 42. This assistance significantly accelerated Iran’s uranium enrichment program, giving them capabilities they might have taken decades to develop independently 2223.

IR5 centrifuges at an Iranian uranium enrichment facility.

The Libya Connection

In 1997, Khan began transferring centrifuge technology to Libya, which became one of his network’s most ambitious clients 74. Libya received 20 assembled P-1 centrifuges and components for 200 additional units for a pilot enrichment facility, with continued supplies until late 2003 724.

By 2000, Libya had placed an order for components for 10,000 P-2 centrifuges to build a cascade, representing what would effectively be a turnkey nuclear weapons program 724. The massive order involved manufacturing facilities in Malaysia, where SCOPE (Scomi Precision Engineering) was contracted to produce centrifuge components that would be shipped through Dubai to Libya 258.

Khan’s network also provided Libya with nuclear weapons designs of Chinese origin, complete with Chinese notes in the margins, showing the extent of the proliferation 724. The Libyan deal reportedly earned Khan over $100 million, demonstrating the lucrative nature of his nuclear black market 176.

Security personnel guard centrifuge components, typical of those supplied by the A.Q. Khan network, from Libya’s dismantled nuclear program.

North Korean Dealings

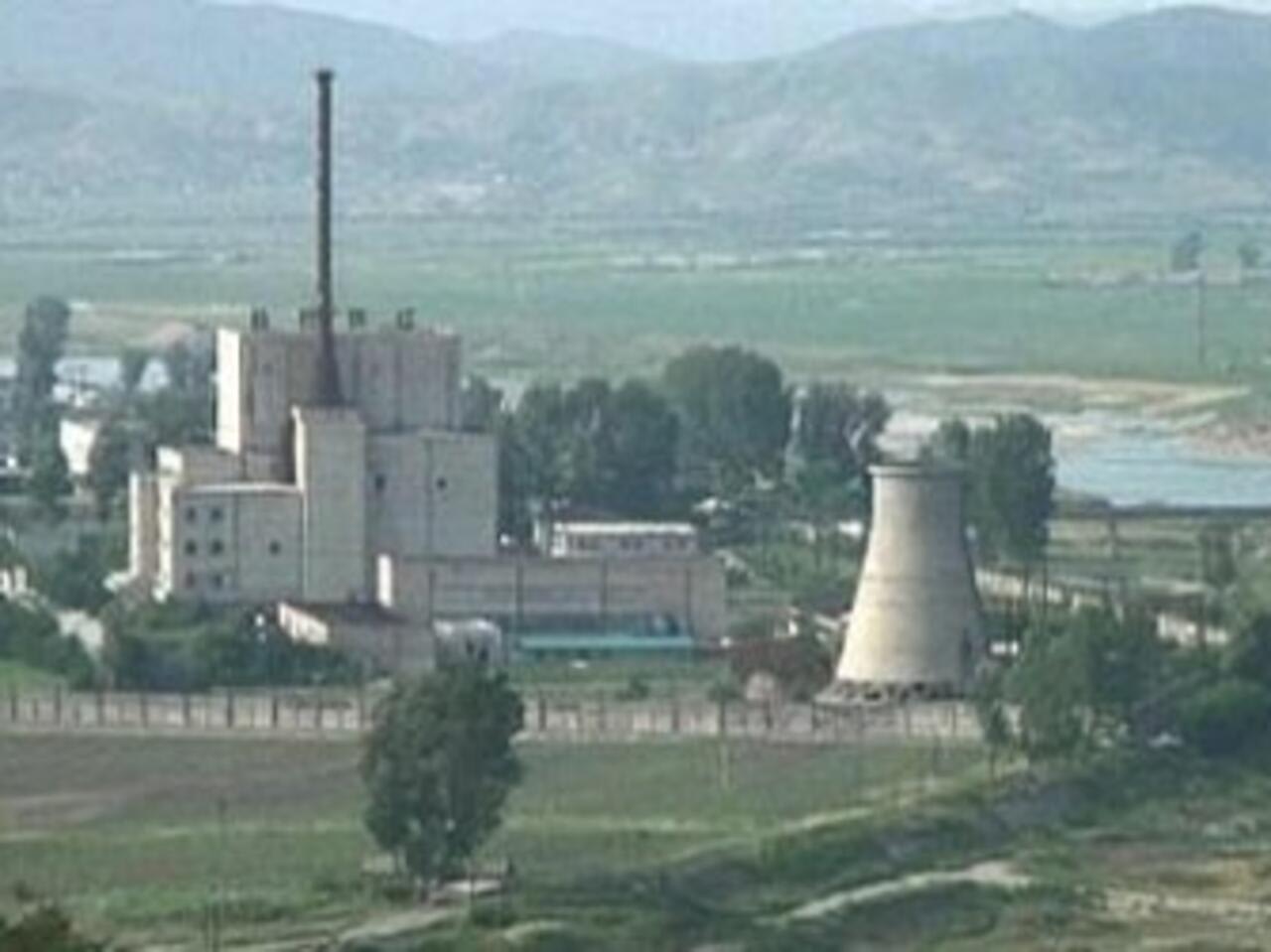

Khan’s relationship with North Korea began in the 1990s when Pakistan started missile cooperation with the isolated nation 47. While Pakistan received No-Dong missiles from North Korea, Khan is suspected of providing centrifuge technology in return, possibly as part of a barter arrangement 48.

By 1997, Khan is believed to have begun nuclear transfers to North Korea, though the exact timing remains uncertain 726. Khan reportedly visited North Korea at least 13 times before his public confession in 2004, using these trips to arrange transfers of nuclear technology 626.

The Pakistan-North Korea relationship helped both countries advance their weapons programs, with Pakistan gaining missile delivery systems while North Korea acquired uranium enrichment capabilities to complement its existing plutonium path to nuclear weapons 410. North Korea would later conduct its first nuclear test in 2006, partially enabled by Khan’s assistance 1410.

Yongbyon nuclear facility in North Korea, a significant site in nuclear proliferation discussions.

Network Structure and Operations

Khan’s proliferation network operated as a sophisticated international enterprise with multiple nodes and supply chains 1619. At its center was Khan himself, who leveraged his position at KRL and his extensive knowledge of nuclear technology suppliers 1727.

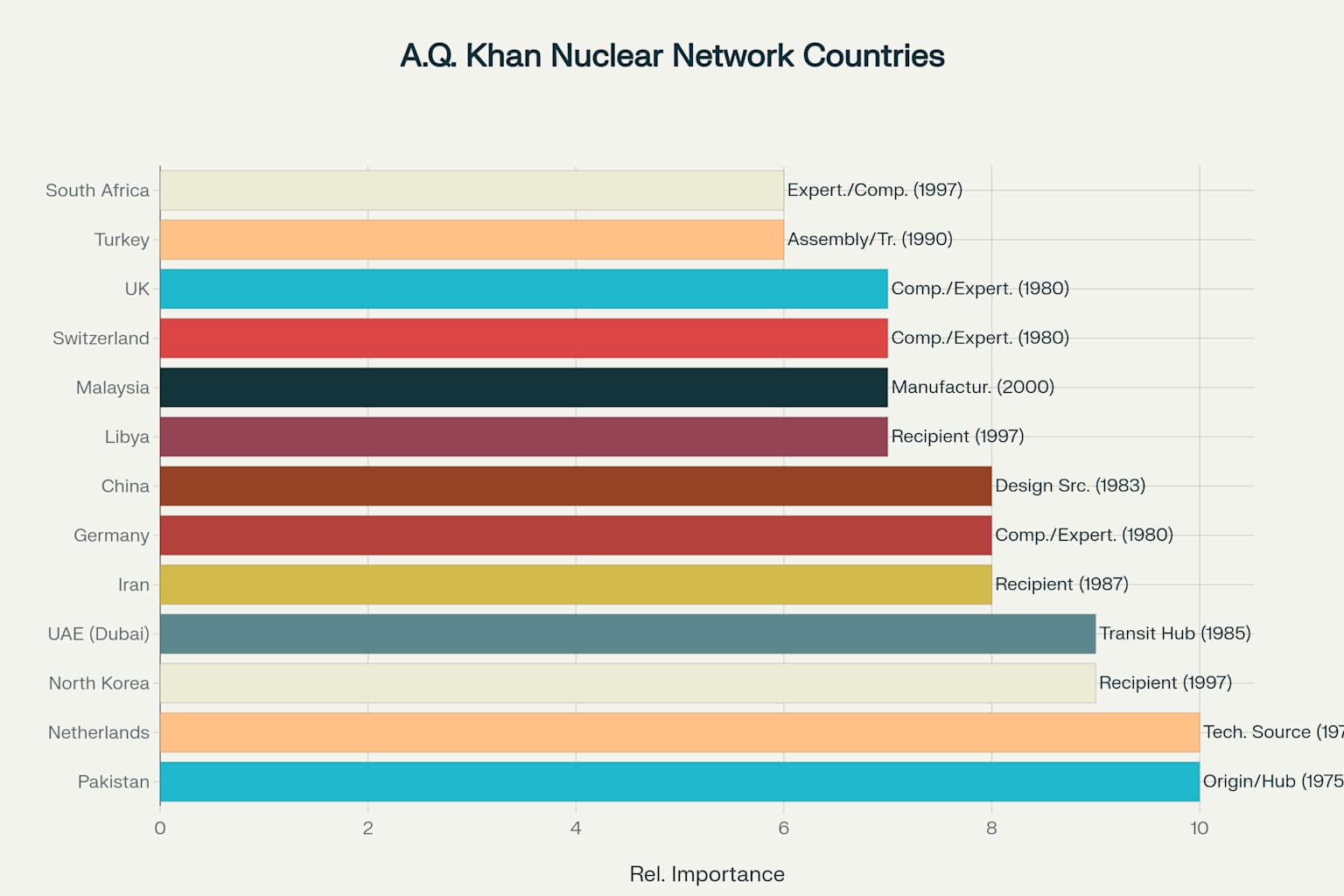

The network had several key operational hubs: Dubai served as the central transshipment point, Malaysia was used for manufacturing centrifuge parts, and Turkey functioned as both an assembly point and transfer location 416. European suppliers from countries like Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Germany provided crucial components, while South African nuclear experts contributed technical knowledge 419.

Khan employed dozens of shell companies, often created for one-time use, and utilized false end-user certificates to disguise the true destination of nuclear components 516. The network operated on a business model that involved huge markups on components, with Khan reportedly earning millions of dollars from his illicit trade 1724.

Countries Involved in A.Q. Khan’s Nuclear Proliferation Network

The Network Exposed

The beginning of the end for Khan’s network came in October 2003, when intelligence agencies intercepted the German cargo ship BBC China en route to Libya 2829. The ship was diverted to the Italian port of Taranto, where officials discovered five containers labeled as “used machine parts” that actually contained thousands of centrifuge components manufactured in Malaysia 2930.

This interdiction was part of the Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI), a U.S.-led effort to prevent the trafficking of weapons of mass destruction 2931. The seizure of the BBC China cargo provided concrete evidence of Libya’s clandestine nuclear program and Khan’s role in supplying it 2430.

Following this discovery, Libya’s leader Muammar Gaddafi decided to renounce his country’s nuclear weapons program in December 2003, cooperating with international investigators and revealing details about Khan’s network 630. Libya’s disclosure provided investigators with unprecedented insight into the scope and operations of Khan’s proliferation activities 1724.

An Italian Coast Guard vessel during a maritime operation, likely related to counter-proliferation efforts.

Confession and Aftermath

Under pressure from the United States, Pakistan removed Khan from his position at KRL in 2001, though this did little to immediately halt his network’s activities 86. In January 2004, Khan was detained and questioned by Pakistani authorities about his proliferation activities 42.

On February 4, 2004, Khan made a televised confession on Pakistani television, admitting to providing nuclear technology to Iran, Libya, and North Korea 3222. In his confession, Khan claimed he acted independently without the knowledge or approval of Pakistani government officials, a claim many experts found dubious 2232.

Despite the gravity of his actions, Khan was pardoned by President Pervez Musharraf shortly after his confession, though he was placed under house arrest 3233. The Pakistani government refused to allow international investigators to directly question Khan, limiting the full exposure of his network 2233.

Abdul Qadeer Khan, Pakistani nuclear scientist, in a formal discussion.

Global Impact and Legacy

Khan’s network represents the most serious breach of nuclear nonproliferation in history, enabling multiple countries to advance their nuclear ambitions 3435. The network demonstrated the vulnerability of the international nonproliferation regime and exposed weaknesses in export controls across numerous countries 35.

In response to Khan’s network, the international community strengthened nonproliferation efforts through initiatives like UN Security Council Resolution 1540, which criminalized the proliferation of WMD to non-state actors 423. The exposure of the network also led to increased scrutiny of dual-use technologies and greater international cooperation in tracking nuclear smuggling 3435.

While many of Khan’s associates were identified, very few faced serious legal consequences 4. B.S.A. Tahir was arrested in Malaysia in 2004 but released in 2008, while European suppliers like Gotthard Lerch and the Tinner family received minimal sentences despite their significant roles in the network 421.

Impact of A.Q. Khan’s Network on Nuclear Capabilities

Final Years

Khan was released from house arrest in February 2009 by an Islamabad High Court ruling, which declared his detention unconstitutional 3336. His release sparked concern from the United States, which warned that Khan still remained a “serious proliferation risk” 3736.

Despite restrictions on his movements and activities, Khan remained a popular figure in Pakistan, where many viewed him as a national hero who had strengthened the country’s security 3738. In his later years, Khan continued to defend his actions, sometimes retracting his confession and claiming he had been made a scapegoat 3839.

On October 10, 2021, Khan died at the age of 85 from complications related to COVID-19 3940. He was given a state funeral in Pakistan, demonstrating his continued status as a national hero despite his proliferation activities 4038. Khan’s legacy remains deeply contested—revered in Pakistan but viewed by much of the international community as one of history’s most dangerous proliferators 3841.

Abdul Qadeer Khan, the Pakistani nuclear scientist, posing for a photograph outdoors.

Lessons and Implications

The A.Q. Khan network revealed how non-state actors could acquire and transfer complete nuclear weapons technology outside of state control 423. This precedent raised serious concerns about the potential for terrorist organizations to acquire nuclear technology through similar black market channels 36.

Khan’s network exploited weaknesses in the global nonproliferation regime, including inadequate export controls, lack of international cooperation, and the dual-use nature of many nuclear technologies 23. The network’s success was also facilitated by the prioritization of other foreign policy objectives over nonproliferation concerns, particularly during the Cold War when Pakistan’s strategic importance outweighed nonproliferation goals .

Today, the impact of Khan’s proliferation activities continues to shape international security dynamics, particularly regarding Iran’s nuclear program and North Korea’s nuclear arsenal 41. The network demonstrates that once nuclear knowledge and technology spread, they become almost impossible to fully contain, creating enduring proliferation risks for the global community 23.

Global Reach of A.Q. Khan’s Nuclear Proliferation Network

Conclusion

A.Q. Khan’s nuclear black market represents one of the most significant proliferation events in history, transforming the global nuclear landscape 27. From his theft of centrifuge designs in the 1970s to the expansion of his network across multiple continents, Khan created an unprecedented threat to international security 923.

The dismantling of Khan’s network in 2003-2004 marked a crucial victory for nonproliferation efforts, but many of its effects cannot be reversed 3523. The technologies and designs he distributed continue to influence nuclear programs in Iran and North Korea, while the methods he pioneered for evading export controls have provided a blueprint for future proliferators 41.

Perhaps most significantly, Khan’s case demonstrates how a single determined individual with the right knowledge and connections can undermine international nonproliferation regimes 27. As nuclear technology continues to spread globally, the lessons from the Khan network remain vital for preventing future proliferation and securing nuclear materials and knowledge from misuse 35.

Various aspects of nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation efforts, from the destruction of WMDs to diplomatic engagement.

Footnotes

-

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Abdul-Qadeer-Khan ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

https://ahf.nuclearmuseum.org/ahf/profile/q-khan/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/10/10/abdul-qadeer-khan-nuclear-hero-in-pakistan-villain-to-the-west ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11 ↩12 ↩13 ↩14 ↩15 ↩16 ↩17

-

https://www.rusi.org/publication/nuclear-black-market-extent-and-countermeasures ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11 ↩12

-

https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/power-and-energy/pakistan-nuclear-weapons-program ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11 ↩12 ↩13

-

https://nuke.fas.org/guide/pakistan/nuke ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7

-

https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/aq-khan-dead-long-live-proliferation-network ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

https://carnegieendowment.org/events/2012/01/the-aq-khan-network-and-its-fourth-customer ↩

-

https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2005/09/a-q-khan-nuclear-chronology ↩ ↩2

-

https://www.csmonitor.com/2004/0202/p07s02-wosc.html ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/pakistan/thief-traitor-smuggler-scammer-how-the-west-remembers-aq-khan/articleshow/86917048.cms ↩

-

https://www.voanews.com/a/a-13-2006-01-05-voa30/330192.html ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

https://isis-online.org/publications/southasia/nuclear_black_market.html ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pakistan_and_weapons_of_mass_destruction ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6

-

https://www.securityoutlines.cz/abdul-qadeer-khan-and-his-proliferation-network/ ↩ ↩2

-

https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/holding-khan-accountable-an-isis-statement-accompanying-release-of-libya-a-/ ↩ ↩2

-

https://archive-yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/fallout-pakistani-revelations-north-korea ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1506\&context=jss ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7

-

https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2005-03/features/turning-blind-eye-again-khan-networks-history-and-lessons-us-policy ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6

-

https://commdocs.house.gov/committees/intlrel/hfa27811.000/hfa27811_0.HTM ↩

-

https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/aq-khan-redux-ongoing-risk-nuclear-proliferation-networks ↩ ↩2

-

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2004-feb-05-fg-khan5-story.html ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

https://www.latimes.com/world/la-fg-pakistan-khan7-2009feb07-story.html ↩

-

https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/iaea-helps-south-african-government-dismantle-illicit-nuclear-network ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

https://thedispatch.com/article/the-lasting-legacy-of-aq-khan/ ↩

-

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/a-look-at-the-life-of-a-q-khan-scientist-behind-pakistans-nuclear-weapons-program ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2005-03/features/turning-blind-eye-again-khan-networks-history-lessons-us-policy ↩ ↩2

-

https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2004/december/interdict-wmd-smugglers-sea ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200405/cmselect/cmfaff/36/36we33.htm ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

https://thebulletin.org/2014/12/a-message-from-tripoli-how-libya-gave-up-its-wmd/ ↩ ↩2

-

https://www.isis-online.org/publications/libya/cent_procure.html ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

https://www.pbs.org/frontlineworld/stories/pakistan/nytimes01.html ↩ ↩2 ↩3